‘I trust you.’

These were the words actress and TV personality Noni Hazelhurst said to portrait artist Jaq Grantford at the sitting of what would become the 2023 Archibald Prize People’s Choice-winning portrait, now hanging in the Tamworth Regional Gallery alongside paintings of Don Walker, Claudia Karvan, and Montaigne.

“And that really put the pressure on,” Grantford says, “Oh my god, I really have to do something she likes.”

The Mornington Peninsula artist made the long trek up to Tamworth for the opening of the Gallery’s leg of the travelling Archibald Exhibit, which will be open until the 23rd of June.

Grantford is dwarfed by her own painting, with Hazlehurst five, six times larger than life. In it, Hazlehurst is painted from the shoulders up, her face in the process of breaking into a smile. She says she almost went too detailed in the rendering, pulling it back in the final stages to something more painterly.

“I love detail, so I have to have very understanding subjects who don’t mind the fact I’ll put everything in.”

Hazlehurst’s face is incredibly finely-painted, in oils, – each line, each flyaway hair laid out on the canvas, but it’s an honesty that befits its subject. Hazlehurst’s face is instantly recognisable, as is her persona, and that certainly didn’t hurt Grantford winning the People’s Choice.

It is a traditional portrait method and medium, executed to a high standard. The Archibald has long since embraced the less traditionalist, less formal styles. Grantford mentions William Dobell’s winning work in 1943 that led to him being sued by two other entrants who claimed he submitted a caricature, not a portrait, being a groundbreaking moment.

But, Grantford says, smiling her style is coming back. “Realism’s coming back – contemporary realism, it’s called – in Europe, in the US, it’s making it quite big.”

But what’s most unusual for a portrait is that there’s something placed between the subject and viewer: a window, its framing dividing up the painting into quadrants, misted over with condensation and dappled with raindrops. Grantford does admit to a conceit with the lighting – the painting, for all its realism, is impossibly lit, with light shining from both the left to illuminate Hazlehurst, but also equally brightly from the front, catching the window frame.

“Well, it’s through-the-window, from Play School,” Grantford says, “It was a nod to that, and I thought that feels very right.”

Like a lot of Aussies, Grantford grew up watching Play School, and like a lot of Aussie mums, she went on to watch it with her own children, and Grantford set out to capture the warmth, the sense of maternity, and security that Noni provides generations of Australians.

“I almost painted the Play School windows,” Grantford says, laughing, “But then I thought no, that’s way too obvious. And also Noni is so much more than that: she’s a serious actor, she’s a mother.”

It’s unusual for a portraitist to put a barrier between the viewer and the subject – but there was a deeper significance to it, Grantford says: it was to show Noni protected and safe.

“With the raindrops, you evoke a sense of life,” Grantford says, before adding “Noni went through flooding, and she’s had bushfires. And when I met her she was displaced because of floods, so I put the raindrops there.”

“But then we’ve got symbols for protection for her.” Those symbols are etched, as with a fingertip, in the condensation on the glass – old world symbols, one Celtic, one an interpretation of the Middle Eastern hamsa, designed to ward off evil.

“Noni found that quite touching actually, because she didn’t know I was doing that.

“I just sort of did it and said ‘Here’s the painting,’ and she was quite moved by that,” Grantford says, “She said it felt unusual for someone trying to do something to try and protect her – because she’s often seen as the nurturer herself.”

“Noni brought in some symbolism as well as she wore the ring on her finger her son made for her – he’s very talented,” Grantford says, “And she wears it all the time and means so much to her so that you know, she wanted that in it, too.”

This is not the first time Grantford has entered, but it’s the first time she’s won – as the saying goes, you have to lose an Archibald before you win an Archibald. And it’s not her first portrait of Hazlehurst; Grantford first promised her a portrait years ago, and painted one with the intent of giving it to her.

“The first time I painted her she was going to have the painting, but then the National Portrait Gallery acquired it!” Grantford says.

“I had to send a very embarrassing message saying ‘You know that painting I said you could have? You can’t have it any more.’”

That first painting built up a layer of trust that allowed Grantford to express herself comfortably. Noni, Grantford said, is naturally very warm.

“She was so lovely. I was saying, ‘Look I’ve got this idea, and you know, let’s do this, you know, can I get this light here and that light there?’ And I would ask her and say ‘Yeah, okay, you happy?’”

“And she said ‘I trust you. Just, whatever: I trust you.’”

“It’s my interpretation of Noni, but I also want her to like it as well.”

This is the promised second painting, and, after it’s finished its tour, it will go to Hazlehurst’s home and hang there – as a sort of apology, but what an apology: an Archibald.

Winning still feels surreal for Grantford. “I’m still pinching myself – I’m surprised my arm’s not covered in bruises. To be selected, and then win the People’s Choice – it’s a double whammy of excitement.”

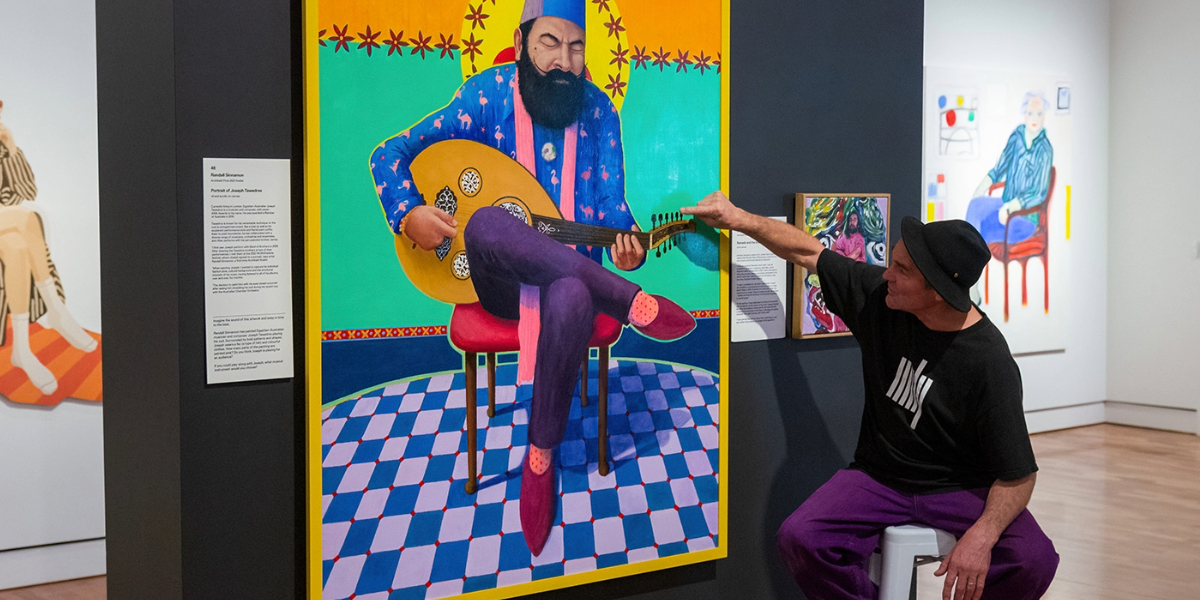

Towards the other end of the spectrum of Archibald finalists for 2023 is Randall Sinnamon’s portrait of Egyptian-Australian multi-instrumentalist, Joseph Tawadros. The Jervis Bay artist – he sculpts, draws, and paints – saw Joseph and his brother James opening WOMAD in Adelaide, and felt he just had to paint him.

“They were on a huge stage, these two Egyptian guys sitting here, all dressed in this wonderful colourful clothing with Joseph with his Salvador Dali-esque type beard,” Sinnamon says.

“Behind them was this very serious orchestra, all dressed in black tie. And the orchestra playing the music that’s been composed by Joseph and his brother.

“And that’s what made me think ‘Why are they so colourful? I want to paint you’.”

After the performance, Sinnamon approached Tawadros at the booth they were selling their CDs from, bought and asked.

“I asked him ‘Hey, you know, has anyone painted you for the Archibald?” Sinnamon says.

“It was funny. He said ‘Yes, but it hadn’t been selected.’ And then he said ‘If you want to have a go at it, have a go at it.’”

It was a matter of staying in constant communication with Tawadros, who was raised in Redfern in Sydney – “He’s got a real Ocker accent” Sinnamon says – but lives in London, until he came back for another round of touring in Australia. Sinnamon had taken photographs, crawled Tawadros’ Instagram page, and set it all up around his studio.

“I had photographs of his hands and his jewellery and all different shots of his face pinned up around the studio.”

“If you walked in there you’d think I was stalking this guy.”

Sinnamon’s portrait is bold, with broad swathes of bright colours. The lighting is harsh, nothing is hidden and the shadows are faint. Tawadros sits, legs crossed, playing his oud, in front of a background of bright orange and green bisected by a line of red flowers, a lemon yellow halo framing his head. It seems flat, but as static as a painting is, Tawadros playing his oud couldn’t be frozen in paint.

“He always wears something colourful,” Sinnamon says, “He’s quite a fashionable character; he’s been on the front page of Harper’s Bazaar in London.”

“I know he likes to wear flamingo shirts – I’ve seen him in one a couple of times now – so I did him in a flamingo shirt.”

But after someone told Sinnamon flamingo prints are being sold “in Kmart for ten bucks” he decided to tweak it a bit; it’s not all flamingos. There’s two camels, a single kangaroo, and a lone monkey in the pattern.

“I started changing a couple of the flamingos to camels. And then I thought of the idea of the camel, and the kangaroo – the Australian-Egyptian connection.”

“And he’s quite a larrikin. Hence the monkey.”

The portrait is mixed media: acrylic as the base, oils on top. Sinnamon normally works in oils for his paintings, but says “It seems those fluoro colours – there’s more of them in acrylic than in oil”. Sinnamon’s other works are quite earthy, grounded, but Tawadros could only be rendered in neon. A portrait is a work of two artists, it seems, both of whom influence the final work.

Sinnamon researched Egyptian tiles and motifs for the patterns in the painting, but eventually feel on the pattern of a dress his partner was wearing.

“I was looking for a little sort of a border type thing, and my partner had a dress on at the time,” he says, “So I chose a little section of her dress, which is the bit that sort of goes around the bottom of the stage, and separates two of the colours.”

But the bit he was putting off to last was the most important part of a portrait: the face. Sinnamon travelled to Canberra to see Tawadros play again.

“I’d been thinking ‘Come on, Joseph, give me the Tawadros face’ backstage before he went on.”

“And he played a bit and closed his eyes – he really got into it, you know?”

Sinnamon ended up seated next to a man who asked him if he was a musician. He told him no, he was, but he was doing a painting of Joseph, and Sinnamon then spent the concert wondering if he should paint Tawadros with his eyes closed.

“When the concert finished, the fella looked at me and said ‘I reckon you should paint Joseph with his eyes closed.’”

“And I said ‘I think you’re right,’” Sinnamon says, laughing. “I went home, thinking ‘you’re not going to be selected in the Archibald with a painting of somebody with their eyes closed.”

“But that was a good thing, because that’s mostly what he looks like on stage, when he’s really in that moment of concentration.”

Sinnamon has entered “six or seven” times before.

“I know the feeling of being rejected, which is a feeling that you just have to get used to anything where you just don’t worry about it, and keep trying.”

“And I’m just happy to be selected this year. It’s a good feeling – you get invited to all the events, I’m here in Tamworth. It’s good to be a part of it.

Thanks to a grant from the University of New England, entry to the exhibit at Tamworth Regional Gallery is entirely free, which is extremely rare among the touring galleries. The exhibit closes on June 23rd.

Like what you’re reading? Support The New England Times by making a small donation today and help us keep delivering local news paywall-free. Donate now.